|

| 20150913,16 4711 |

The

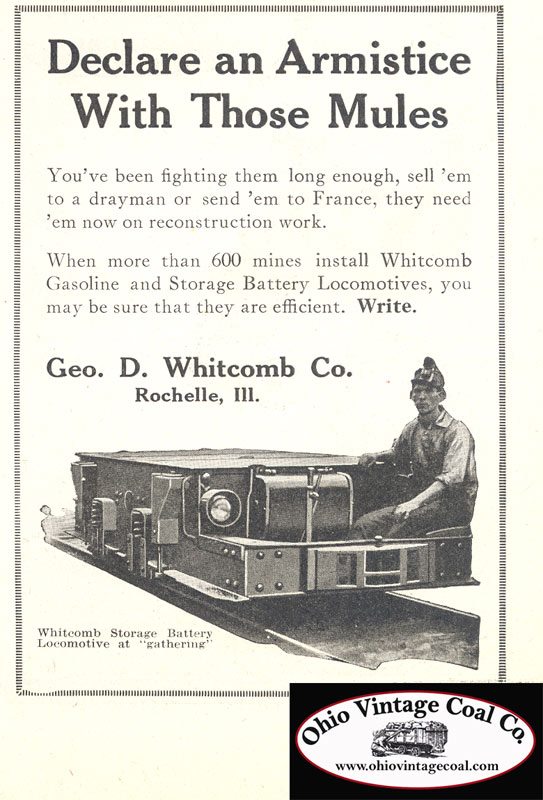

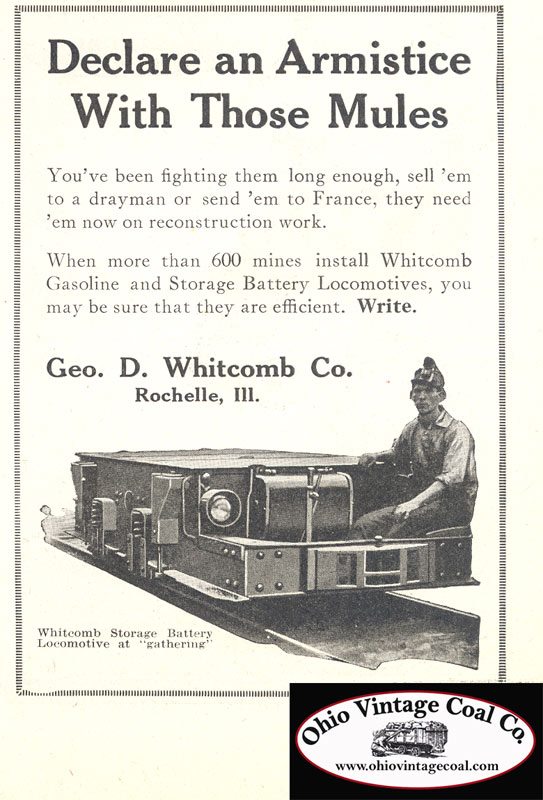

Rochelle Railroad Park includes a static display of a Whitcomb locomotive. In 1878, George D. Whitcomb started manufacturing coal mining and knitting machinery, and in 1892 he incorporated his business as the George D. Whitcomb Co. In April 1906, they built their first gasoline-powered locomotive for mine use. (Update: Steve O'Connor indicates

1910 is probably a more accurate date.) In 1907, production was moved from Orleans and Ohio Streets in Chicago to Rochelle, IL because his largest knitting customer was there. During WWI, most of the output of the plant were government orders. In 1929, they designed and built the largest gasoline-electric locomotive that had been offered to American railroads. Soon after, they started producing diesel-electrics.

Starting in 1927, the Baldwin Locomotive Works helped Whitcomb sell locomotives oversees, So when it went bankrupt in 1931, it was aquired by Baldwin. WWII again produced heavy government demand for their locomotives, and the size of the plant was doubled in 1942. But in February, 1952, production was transferred from Rochelle to Baldwin's Eddystone Works in Pennsylvania. The name on the industrial line of locomotives was changed from Whitcomb to B-L-H in December, 1952. That line of locomotives seized production in March, 1956. (

Wippany,

Wikipedia)

Taplines has a nice collection of pictures arranged from smallest to largest.

A 1922 Sanborn Map indicates the plant was in the northeast quadrant of Second Street and Fifth Avenue. A 1939 Aerial Photo of that area shows the plant was still on the eastern edge of the town.

There are still industrial buildings at

that location so I wonder what is made there now.

When I noticed it had

poling pockets, I looked at all four corners to try to find the best light. I picked the southeast corner not only for the light but because it had been "ripped." It is had to imagine what caused the force needed to "tear" steel. Note the side rods on the wheels.

Update:

several photos of the plant. (

experimental link)

Republic Locomotive says they are "the only manufacturer of all-new industrial locomotives in North America." I found their description of

why AC traction motors have about double the adhesion of DC traction motors to be rather fascinating.

Steve's comment:

HOW TO HIDE A 65 TON LOCOMOTIVE

“Whitcomb Diesel locomotives built here in Rochelle have played an important part in this war on almost every front. Being smokeless and easy to camouflage against air attacks these locomotives have been extensively used where standard coal burning locomotives proved impractical.

In our January 12th 1945, issue of the Leader we printed an interview with W.F. Eckert, chief engineer at Whitcomb in which he told how Whitcomb built locomotives had solved the English and American transportation problem in North Africa, German bombers had blasted most of the regular locomotives as their smoke was easily spotted by the fliers.

Rochelle Whitcomb diesel locomotives were then camouflaged as regular box cars. In the make up of trains the location of the “ box-car-locomotive” was constantly changed to elude the Germans in their bombing attacks.

The plan proved very successful, and it has been credited as one of the major forces in the British success in the drive from Egypt to Tunisia during the latter four months of 1942 and early 1943.”

The Rochelle Leader

May 4, 1945

|

| Steve OConnor comment for above posting |

|

Steve OConneor comment on a posting

The Whitcomb factory in Rochelle circa 1930's. |

Steve OConner comment:

Whitcomb Enters WW II

“During the latter part of 1940 we were asked to design a locomotive which could operate successfully through desert sand storms and keep cool with the thermometer registering 125 F. in the shade. The only other known factors, besides the gauge of track was that they needed all the power we could give them but the weight had to be reduced to the absolute minimum. That is just about as contradictory as wanting the strength of a draft horse in a Shetland pony. As the boys in the engineering department were only working about 60 hours a week at that time, they decided there wasn't any particular reason why we couldn't tackle the problem. By actual count there are 10,756 different items necessary to build that Diesel electric locomotive, and the fact it is still in production offers conclusive proof that the engineers did their work well. Incidentally, in that count the Buda diesels, Westinghouse Electric Equipment, the Young Radiators and all other materials purchased in a finished state are merely figured as individual items. The balance had to be designed, detailed, weights estimated, purchased, machined, fabricated, assembled, crated and the completed product sent on its way. We received the actual contract shortly before Christmas and the first units were operating in Egypt the following May. That is less than half the normal time required on a completely new design. Certainly there isn't much I could say to further emphasizes the splendid spirit of cooperation which not only exists within the Whitcomb organization but also extends out among all of our suppliers. They have done a grand job and all of us know it.”

H. G. HeulguardVice President, General ManagerWhitcomb Locomotive CompanyThe Rochelle News, January 26, 1944

Steve's comment:

Whitcomb 65-DE-19a locomotives built in Rochelle, Illinois, WW II Trier Germany March 1945.

At least a couple of the military models have survived.

A

video of a Buda running. One article mentioned they had trouble with the cylinder heads. Skip to 3:33 in

an Army video to see the locomotive in action.

Steve's comment:

October 10, 1940 Dekalb, IL. Brand new Whitcomb switcher built in Rochelle just 20 miles west of Dekalb. WAITE W. EMBREE Collection, Northern Illinois Regional History Archives, NIU. Note the Embree name on the hardware building in the background. Waite Embree took numerous photos of rail activity around Dekalb at this time. http://www.ulib.niu.edu/reghist/regionalhistory.cfm

|

Steve OConner posted

This page ad is from the 1947 Locomotive Cyclopedia which my Dad bought new. I found it when cleaning out his house and thought it might be of some value. |

|

Steve OConner posted

More from the 1947 Locomotive Cyclopedia. |

|

Steve OConner posted

Scan of an original builder's photo, Whitcomb factory in the background. |

|

Steve OConner posted

A shipment of Whitcomb locomotives built in Rochelle photographed in Dekalb, 1949. Waite Embree collection, NIU. The Dekalb coal tower in the background.

Looks like some of CN's 75-ton 75-DE-12c types being delivered. All eighteen were returned to Whitcomb in 1950 and 17 were sold to Rock Island. |

Steve OConnor

posted four photos with the comment:

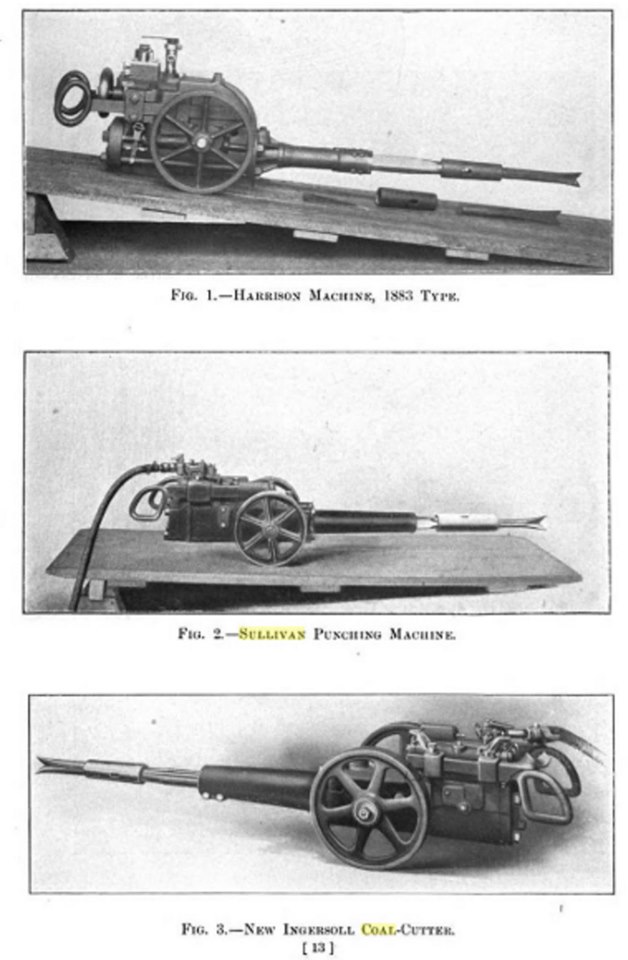

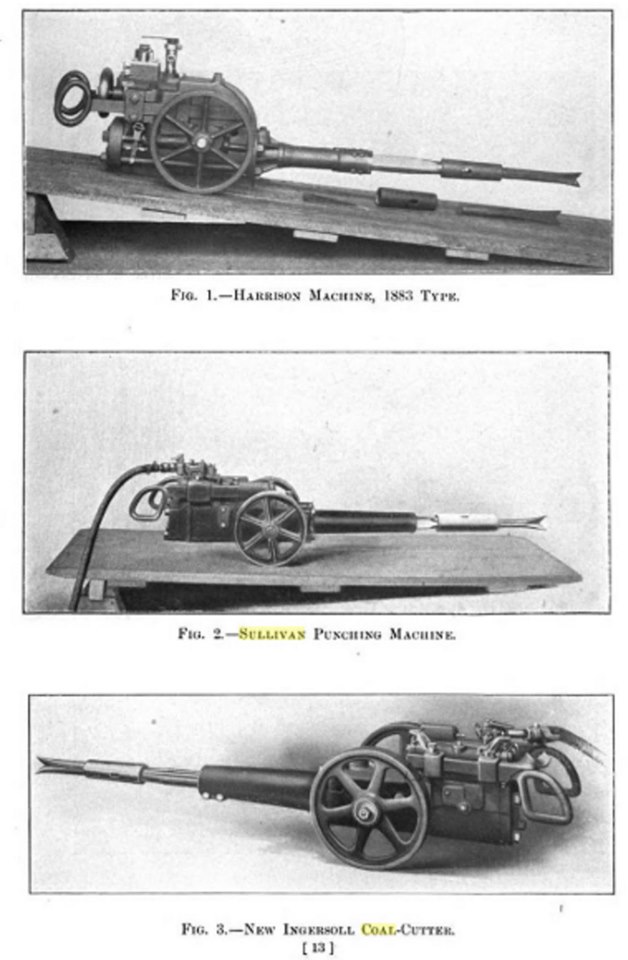

Whitcomb and the Illinois Coal Mining Industry - PART 1 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -Before 1878 the only way to remove coal from a shaft mine was to blast it out. But before you could reach for the black powder you had to undercut the coal seam. The only way this could be done was to have a miner lay on his side for hours on end swinging a pick to chip away a slot under the coal seam. Once done holes were hand drilled 3-5 feet deep at the top of the seam and black powder charges packed in with a fuse. If the seam was not undercut the impulse from the explosion would go into the roof, fracturing it and creating a great risk of roof collapse - the number one cause of death in coal mines. Then entered George Dexter Whitcomb - - - - Early in life, George Dexter Whitcomb, moved with his family, from Brandon, VT, to Kent, OH. Here he started his business career, engaging with the Pan-Handle Railroad, as purchasing agent. While in this employment, the air brake was invented, and he became very interested in its development. He co-operated in making the tests of the Westinghouse Air Brake and was one of the original stockholders and members of the Board of Directors of the Westinghouse Air Brake Company, when it was organized.

In 1868, George and his wife Leadora had a son, William Card Whitcomb. As an adult, William received an engineering degree from the newly founded, University of Southern California in 1889. Upon graduation he would join to assist and improve his father's business.

George left the Pan-Handle Railroad about 1870, moving to Chicago, where he took charge as manager of the Wilmington Coal Mining and Manufacturing Company's mines at Braidwood, IL. He also managed the Wilmington Coal Association which handled the output of the Braidwood, IL coal field.

He continued in charge of these mines until about 1878. While there, the Harrison Mining Machine was brought to his attention. The concept of the power pick was that of a hand-held machine controlled by one person and operated by compressed air. He saw merit in the idea and took hold of the machine. He developed and perfected it into what is now known as the "Puncher Machine." This machine was the first successful undercutting machine put on the market in this country. He resigned his position with the coal company about 1878 to devote his entire time and attention to the mining machine business. More to come . . .

Nick Koba Jr. thanks for posting as a braidwood coal miner I never knew this piece of History I hope you don't mind if I copy this for our local historical Societies .

Steve OConnor You are more than welcome to share. Somewhere I read that the introduction of these undercutting machines led to some violence in the Braidwood coal fields from miners who saw it as a threat to their jobs but I can't find it now. Also there is a lot more history to come about this company and coal mining.

Nick Koba Jr. the Braidwood miners were a routy bunch and Braidwood was also the birth place of the UMWA it was had the first local is was Local Number 1 . a lot of history in this coal mining area . I have a book being printed right now about the local strip mines of this area from 1927 to 1974 when all mining stopped here .

Nick Koba Jr. Steve OConnor this company in Braidwood that he work for also owned the Diamond No. 2 Mine on Feb. 16th. 1883 heavy rains melted heavy snow and it broke into this coal mine flooding it between 69 to 74 men & boys were killed a month later the water was pumped out and 28 bodies were removed & 41 to 46 remain in the mine . there is a munument on the North side of Rt 113 a mile West of I-55 to these men & boys .

Michele Enrietta Micetich There was a serious miners' strike in 1877 in Braidwood which led to the importing of Italian and Bohemian/Slavic miners to our area. Whitcomb left at that time.

Skip Luke We used coal equipment to mine Trona (soda ash) in southwest Wyoming ..... Conventional sections used the coal cutter, although it cut a vertical slot in the middle of the face instead of undercutting. It was mounted on a Joy self-propelled chassis. we also had continuous miner sections. Mine 1600 feet deep, seam went for many miles.

|

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

|

Steve commented on his post

As this chart shows, mechanized mining rapidly replaced hand work. In 1891 only 6.7% of bituminous coal was machine mined. By 1900 over 25% was done by machine. |

Steve OConnor

posted three images with the comment:

Labor Agitation and the Introduction of Mechanized Mining - the Braidwood Illinois Experience. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Why did Braidwood become home to the Mine Workers’ Union Local #1 which was the first Miners’ Union in Illinois? It led to the unionization of all states that mined for coal. Maybe because Braidwood was also home to the nation's first successful mechanized mining machine. George Whitcomb came to Chicago around 1870 and as I already posted he took charge as manager of the Wilmington Coal Mining and Manufacturing Company's mines at Braidwood, IL. He also managed the Wilmington Coal Association which handled the output of the Braidwood, IL coal field. During this time he also developed the Harrison mining machine. I can find documentation that the Chicago, Wilmington and Vermillion Coal Company were using these machines by 1881. Before these machines existed hand mining required skill, and young miners usually served an apprenticeship under a relative. Lying on their sides, miners first used a pick to undercut the coal three to four feet deep. Undercutting required two to three hours each shift, and standing water often made the task particularly unpleasant. Based on his knowledge of the coal seam, the miner then chose the appropriate places to manually drill the coal face and tamp the holes with explosives. Well placed, the subsequent blast dislodged the coal as far back as the undercut. Poorly placed, the shot broke away little or no coal, and dropped the material in a solid block. This was known as a hung shot. Careless or unskilled blasting preparations could produce a blown-out shot that suspended and ignited the coal dust. After shooting, miners loaded the coal into a mine car, set timber roof props, and extended the track for the next cycle. (https://www.wvencyclopedia.org/print/Article/1835 ) The introduction of mechanized mining eliminated the need for skilled miners and his job security went with it. Was this the incentive that formed the United Mine Workers of America?

|

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

Steve OConnor

posted two images with the comment:

Whitcomb and the Illinois Coal Mining Industry - PART 2 - - - - - - - - Whitcomb's introduction of the first successful undercutting machine in 1878 gave them a monopoly - a short lived monopoly. Soon, two older and larger mining equipment manufacturers had jumped into the field; Sullivan (head office in Chicago) and Ingersoll-Sergeant ( New York City ) - - - - - COMPRESSED AIR - - - - The power source in these early days was compressed air which created problems. First, the coal mines had to invest in a powerhouse to run an air compressor and this was a large investment. Second, the deeper the mine the longer the air pipes and lines resulting in friction losses in air pressure at the coal face. But even with these problems by 1891 there were 545 compressed air puncher machines in coal mines and by 1902 that number grew to 3,185. But there was a new animal on the market - electric-driven chain undercutters.- - - - - ELECTRIC POWER - - - - In itself, the electric-driven chain undercutting machine did not represent a larger threat to Whitcomb than the compressed air units of Sullivan or Ingersoll. But a new development in another aspect of coal mining did represent a HUGE threat to Whitcomb that could put them out of business if they didn't do something quick. More to come.

|

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

Steve OConnor

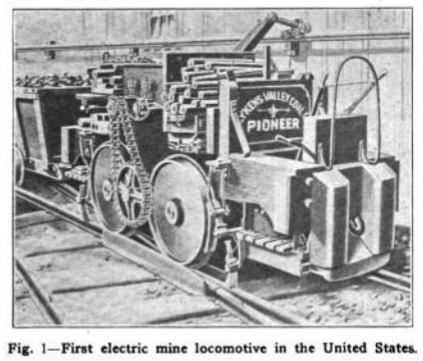

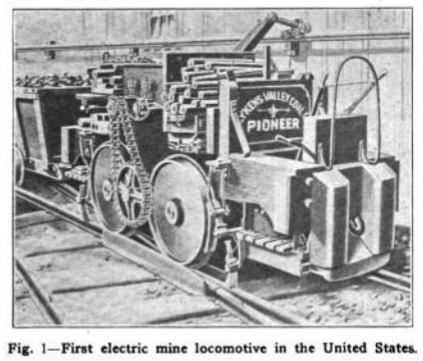

posted three photos with the comment:

Whitcomb and the Illinois Coal Mining Industry - PART 3 - - - ENTERING HAULAGE - - - On July 26, 1887 the first electric mine locomotive in the United States entered service in Pennsylvania. In 1888 the first electric mine locomotive in Illinois began operating at the Number 3 mine of the Chicago, Wilmington & Vermilion Coal Company at Streator made by the Sperry Electric Mining Machine Company of Chicago. By 1904 every important mining district in the state had at least one mine using electric locomotives. Hauling coal out of a mine was never Whitcomb's goal. As long as they could sell compressed air undercutting machines, haulage was not their market. But when electric undercutting machines hit the coal industry Whitcomb now faced a problem. Their customer base could only undercut coal with compressed air. Competing coal mines with electric power could undercut coal and haul it out of the mine with the same power source. Whitcomb realized that if they could not offer their customers some way to also haul coal out of their mines they were at a severe disadvantage and it would only be a matter of time before they would be out of business. Some how they had to develop coal mine haulage that could compete against electric locomotives.

|

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

Steve OConnor

posted four photos with the comment:

Whitcomb and the Illinois Coal Mining Industry - PART 4 - - - THE FIRST SUCCESSFUL INTERNAL COMBUSTION MINE LOCOMOTIVE - - - - When Whitcomb looked at mine locomotives the decision to build an I.C. was made by the son, William Card Whitcomb. The father, George had moved to California on account of his wife's health and Will had essentially taken over by 1900. Electric locomotives required a huge investment in boilers, steam engines to drive the dynamos, the dynamos themselves and miles of electric cables. These overhead cables were a source of sparks that could ignite methane (which is lighter than air) that accumulates at the ceiling where the contact wheel runs on the overhead wire in a coal mine. Also the rail had to be bonded as it carried current in it and it had to be carefully centered with the overhead wire which needed special hangers to attach to highly irregular mine roofs. Electric rail systems were by far the most expensive to build and maintain. COMPRESSED AIR LOCOMOTIVES - - - another option was compressed air locomotives but these also required immense investment in boilers, steam engines and high pressure air compressors. The large air tanks needed to sustain any kind of duration made these locomotives difficult to fit in coal mines and needed recharging stations throughout the mine. The increase of pressure to over 1,000 psi to improve range made maintenance a headache as piston seals would fail and connections leaked making these systems less than efficient. Also, these were already made by older, larger and experienced companies like the H. K. Porter Company and Baldwin that Whitcomb had no chance of competing against. So the only option was a new power source called the internal combustion engine. For Whitcomb, this would be powered by a new fuel, the byproduct of Kerosene production - gasoline. More to come.

Skip Luke Gasoline + mine = catastrophe.

Steve OConnor William Whitcomb and his chief engineer, William Eckert received patents for spark arresting exhaust systems to prevent igniting methane fumes in coal mines, and also engineered ways to safeguard the gasoline tank from impacts.

Steve OConnor https://patents.google.com/patent/US1055845

|

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

Steve OConnor

posted three photos with the comment:

Whitcomb and the Illinois Coal Mining Industry - PART 5 - - - SUCCESS - FAILURE - THEN SUCCESS - - - Whitcomb's first gasoline mine locomotive was simply a car engine, clutch and transmission with a frame built around it that was shipped to the Kolb Coal Company in Mascoutah, Illinois and it only saw very light duty. The time was April, 1906. The appearance of their first generation locomotive and their second generation are vastly different due to the vertical car engine sticking up like a sore thumb. Because this first attempt continued to operate without any major problems they decided to build another one which was sent to Kentucky where the duty was much more severe. - - - FAILURE - - - That unit was a complete failure as it had to pull tons of coal up a grade. For about 3-4 years the owner was constantly having to rebuild it and eventually it was junked. During that time Whitcomb experimented with car engines, marine engines, different clutches and transmissions and finally designed and built their own engine - a flat four cylinder which gave the unit a much lower profile more fitting for a coal mine. Details completely lacking from all the literature about their new engine were the compression ratio and any details about the gasoline to be used. There probably was a reason for this. More to come.

|

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

Steve commented on his post

The coal mine where the first Whitcomb gasoline mine locomotive went. |

Steve OConnor

posted three images with the comment:

Whitcomb and the Illinois Coal Mining Industry - PART 6 - - - THE FUEL PROBLEM - - - The article from the July 19, 1913 Coal Age is the only one I can find where a Whitcomb engineer discussed the engine development problems on their first locomotives and details are few. But during research of the history of gasoline I found that others ran into problems also. - - - ENGINE BASICS - - - First, some basics about gasoline engines will help the reader understand what engine pioneers like Whitcomb were up against. Compression is the key to power and efficiency for an internal combustion engine. According to the Otto Cycle ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Otto_cycle ) the higher the compression the more power and efficiency you can get from the same amount of fuel. But, there is a limit to how high gasoline/air mixture can be compressed before it will create problems. Normally, gasoline burns at a controlled rate initiated by the spark plug so that when the piston is coming up on the compression stroke the expansion of the burning fuel is timed to push the piston when it is beginning to travel back down on the power stroke. But when gasoline/air mixture is compressed too high it will heat up and actually explode before the spark plug fires and the pressure wave will oppose the piston coming up on the compression stroke. This can place enough stress on the engine to damage parts or burn holes through the piston from the extreme heat. - - - OCTANE RATING - - - All gasoline sold today is measured and sold according to its octane rating ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Octane_rating ). But in 1906 when Whitcomb was trying to get a gasoline engine to survive the extreme duty of a coal mine, nobody knew anything about detonation or octane resistance to detonation. The Wright brothers had to use the same gasoline that cars burned in 1903 because aviation gasoline did not exist. In fact, when the U.S. entered WW I in 1917 we became the principal suppliers of gasoline for the Allies and combat planes started falling out of the sky because our gasoline was of inferior octane, but nobody knew that because nobody had developed an octane rating system. - - - STRAIGHT RUN GASOLINE - - - The gasoline of 1906 was a byproduct of the distillation of a crude oil from some oil field that was producing Kerosene. Kerosene was the prime objective, not gasoline because kerosene was how nations were lighting their homes. Gasoline production did not surpass Kerosene until 1916 in the U.S. The gasoline that companies like Whitcomb, the Wright Brothers, Ford, Harley Davidson, Dodge, etc. were stuck with was called a straight run gasoline that was a simple distillate and the quality was entirely dependent on what oil field it came from. This crap shoot could kill a pilot if he put an inferior gasoline into a fully loaded combat aircraft and tried to get it off the ground before he ran out of runway with his engine detonating. Whitcomb, like the Wright Brothers and Henry Ford, undoubtedly had to discover by trial and error how high they could push their compression ratio and still survive somebody running a tank of inferior gasoline through the engine. The octane rating scale would not be introduced until 1930 and every tank of gas before this was measured in terms of boiling points. Boiling points was a way to guess how well the gasoline would vaporize and vaporization was thought to be the single most important quality of a fuel. It is estimated that the octane rating of the gasolines that Whitcomb and everybody else had to use was down around 50 and this pushed compression ratios down below 4:1. More to come.

|

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

Steve OConner

posted seven images with the comment:

Whitcomb and the Illinois Coal Mining Industry - PART 7 - - - THE MOVE FROM CHICAGO TO ROCHELLE. During this time Whitcomb had also engaged in building knitting equipment. I don't know how or why, perhaps one of their engineers came from the textile industry. All of the Rochelle newspapers from this era were destroyed in a fire and no company history covers this. Whitcomb's largest knitting machinery customer was Chicago-based Vassar Swiss Underwear Company. In 1903 Vassar was having Union troubles and as was common they decided to move to Rochelle after given a $22,000 gift as incentive. In 1907 Whitcomb moved to Rochelle from Chicago. The most likely reasons why they moved were they needed a larger plant, they needed rail access for their new locomotive line and staying close to Vassar kept that income fairly secure. Neither Vassar nor Whitcomb would have a union while in Rochelle. Vassar would leave Rochelle and move back to Chicago around 1913. Whitcomb after being bought would get a union around 1940.

|

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

|

| 6 |

|

| 7 |

Patrick McNamara SCABS

Steve OConnor This was a common practice back then. EMPLOYERS ASSOCIATIONS

"During the 1920's, citizens' committees were formed in a number of cities including Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, and San Francisco. Generally they were formed by employers' associations in order to raise funds, and to secure the cooperation of the nonemploying public, for an antiunion campaign. . . . . In Chicago, Cleveland, and San Francisco, citizens' committees, organized by employers' associations, raised millions of dollars to wage a campaign to eliminate the building unions. In such a campaign, building contractors, real-estate interests, and bankers were an important element in enforcing a buyers' and credit boycott against union employers in the industry (the citizens' committee is a device for organizing business groups to carry out a campaign against labor organization and the economic program of unions. It is usually a temporary organization, born out of the fear that labor organizations may have adverse effects upon local business, payrolls, and employment. Through such fear it is able to enlist the support of real-estate owners, professional persons, small retailers, farmers, and other nonemploying groups. Often economic pressure in the form of a threat by an employer or employers to move the business to another locality causes local business groups to organize and exert pressure upon local officials and public opinion in order to break a strike or to eliminate labor unions). . . . As the personnel manager of the Goodyear plant in Gadsden, Alabama, has explained, it is much easier to organize community sentiment in favor of a company in a small community than in a large one. That is true because a small community is so dependent on the company's payroll. . . . The effectiveness of the threat to move lies not only in putting economic pressure upon small, independent businessmen to oppose the union but in forcing the government officials to side with the company. As the experience of the Remington-Rand Corporation in Syracuse and Ilion, New York, during its 1936 strike indicates, it is easier for a company to sway public officials in small cities than in large ones. . . . Under demand from the Citizens' Committee group to cooperate or resign, the mayor and the chief of police of Ilion were forced to appoint and fully equip about 300 special deputies, after which "law and order" broke loose in Ilion. The mayor explained that, as one of the largest property owners in Ilion, he was afraid of the Citizens' Committee, which included the bankers, because "he could easily be a ruined man and have nothing left but his hat, coat, and pants if these people were to clamp down on him as they were able to do and in a manner which he felt fearful they would do." Some merchants also informed the union members that they feared retaliation by the Citizens' Committee unless they went along with that group).

Tactics similar to those of the Remington-Rand Company were used during 1935 by the Brown Shoe Company, third largest shoe manufacturing firm in the country. The Brown Shoe Company then operated 14 shoe factories, one in St. Louis and the rest in small towns in the Middle West where the plants had been built with funds subscribed by representative citizens. The typical agreement provided for a certain sum of money to be furnished by the citizens of the town for the erection of the factory, which the company uses free of charge and will later own when it has spent a fixed minimum sum for labor in the plant during a specified period, usually 10 years. Often there is provision for a rebate of all taxes, business fees, and water rates during those 10 years. Approximately one third of the company's machinery is leased from shoe-machinery manufacturers and the rest can be easily moved to another town. Groups of citizens in small towns around St. Louis are constantly seeking to obtain one of the company's plants for their community.

Under such circumstances, the payroll of the company is the town's chief source of income, and the merchants and public officials of the town, many of them subscribers to the fund for the erection of the plant, are deeply interested in keeping it open and in operation. The economic threat to close the plant and move the work to another small town is sufficient to frighten the whole community. It was the closing of the plant, the threat to move, or the actual movement of machinery, that led in 1935 to the formation of citizens' committees in four small Illinois towns where the company had plants. In these towns, pressure was put upon union members by such methods as withdrawal of merchants' credit, solicitation by the citizens' committee of workers' signatures to an agreement to return to work under "any conditions stipulated by the Brown Shoe Company officials," vigilante attacks upon union officials, and the discharge of union sympathizers by local businessmen. Labor spies and corps of special police were also used. As a consequence of such tactics, the union was eliminated from these plants of the company."

Richard A. Lester, Duke University

Economics Of Labor, 1941

p. 651-656

[The remaining comments are not worth repeating.]

Steve OConnor

posted five photos with the comment:

Whitcomb and the Illinois Coal Mining Industry - PART 8 - - - HAULAGE PRODUCTION AND THE CHERRY MINE DISASTER. The only reference I have found to company history during the transition from Chicago to Rochelle is from an interview in the local newspaper in 1943 with William Eckert. He was the head of engineering for Whitcomb and what little information he gave in the interview is in this paragraph - - - "In the meantime Eckert had quite a deal to do with the improvement of the knitting machines, which at that time had its largest customer in the Vassar Knitting Company of Rochelle. Many of the machines are still in use. In 1907, Whitcomb decided to move from Chicago to Rochelle and the first factory was opened in the building now used by the Rochelle Furniture Co. Here the company grew in activity, shifting steadily from knitting machinery to stressing production of mining machinery and gasoline locomotives, and then in 1912 specializing only in the building of locomotives." - - - So Whitcomb's entire compressed air mining equipment product line was gone by 1912. Their entry into mine locomotives saved their company and this was accelerated by conditions in the coal mine industry. - - - THE CHERRY MINE DISASTER - - - On Saturday, November 13, 1909, nearly 500 men and boys and three dozen mules were working in the St. Paul Coal Company mine in Cherry, Illinois. An electrical outage earlier that week had forced the workers to light kerosene lanterns and torches, some portable, some set into the mine walls.

Shortly after noon, a coal car filled with hay for the mules caught fire from one of the wall lanterns. Initially unnoticed and, by some accounts, ignored by the workers, efforts to move the fire only spread the blaze to the timbers supporting the mine.

The large fan was reversed in an attempt to blow out the fire, but this only succeeded in igniting the fan house itself as well as the escape ladders and stairs in the secondary shaft, trapping more miners below. The two shafts were then closed off to smother the fire, but this also had the effect of cutting off oxygen to the miners, and allowing the “black damp,” a suffocating mixture of carbon dioxide and nitrogen, to build up in the mine. Eventually 259 men and boys died. The disaster stands as the third most deadly in American coal mining history. The increase in the next two years in conversion to mechanical haulage is the greatest by percent in the history of Illinois coal mines. Whitcomb was a direct beneficiary of this disaster.

Nick Koba Jr. from what I have heard they were stil useing mules at the caol mine in South Wilmington , Illinois when the mine shut down in 1954 and they were put into pasture in a fenced field on the North side of Rice Road as they were still alive and eating grass along the fence in 1967 when when I moved near there.

Steve OConnor Mules were a hazard. They could become uncooperative and backup a car and crush a man between them. It would be hard to blame the mules. The life of a mine mule was terrible. They spent most of their lives below ground and were often mistreated and neglected. The Society to Prevent Cruelty to Animals (SPCA) made mine mules one of their earliest concerns.

https://www.historylink.org/File/8651

Steve OConnor HUMANE AGENT RESCUES BESS; TO MAKE ARREST

“Bess,” the mule which worked 24 hours a day in the Pacific Coast Coal Co.’s mine at Franklin, Wash., is enjoying a much-needed rest today as a result of prompt action by the King County Humane society, following publication of an article regarding her in The Star.

An arrest will be made at the mine today, as a consequence.

Fred L. Boalt, The Star’s special writer discovered “Bess” while “covering” a mine accident at Franklin. He found that the company worked its mules until they die; instead of getting more and working them in shifts. It was cheaper.

Mrs. S. C. Griggs, secretary of the Humane society, visited the mine with two officers Friday. She immediately ordered Bess to the barn.

“The mule had worked two weeks without a rest,” Mrs. Griggs said.

|

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

|

Nick Koba Jr. commented on Steve's post

Photo of the Cherry Mine display in the Cherry Library |

|

Steve OConnor posted

Whitcomb locomotive, Pearl Harbor. During WW II these locomotives hauled munitions from the Naval Ammunition Depot Oahu to Pearl Harbor for the U.S. Navy. After December 7, 1941 photography at Pearl Harbor was strictly regulated and these photos were saved from a dumpster at a Naval office at Pearl Harbor. |

Steve's comments in a

posting about the

Coal Valley Mining Company explains that one reason why mules were replaced by Whitcomb mine locomotives is that the hay in the stalls for the mules was a fire hazard: "

The Cherry Coal mine disaster in Cherry, Illinois was started from kerosene oil dripping onto a hay stall for mine mules."

Steve is building

an album of photos concerning the Whitcomb Locomotive. And he has

an album with 72 photos of the building with the comment:

From 1907 until 1952, Rochelle was the place of manufacture for Whitcomb locomotives. These photographs were taken of the former Whitcomb factory in the summer of 2012 by myself. The interior photos were taken 10-24-2015 when Behr Metals owned and operated the building as a recycling business until closed at the end of October, 2015.

In the comments of this

posting by Steve is several WWII Whitcombs.

Steve's

posting has pictures of Whitcombs used to support Perl Harbor.

Flickr of a 75 tonner. A

Flickr Album of photos including

Purdue's.