|

| USACE via EncyclopediaOfAlabama |

|

| TennTom |

|

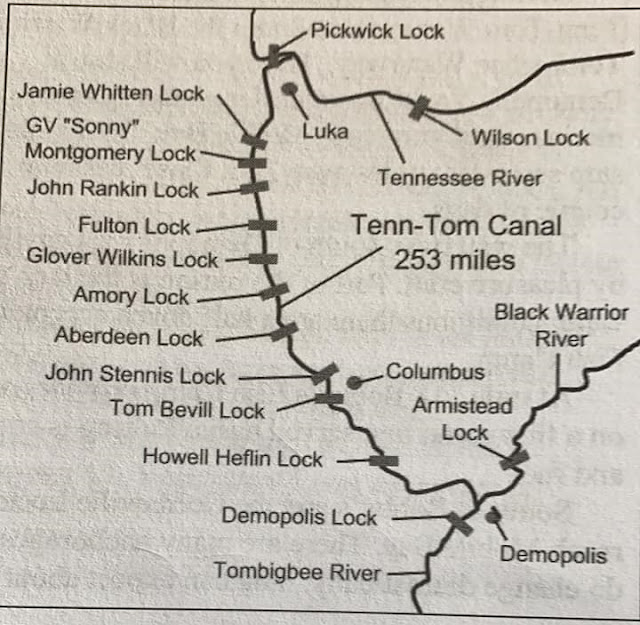

| Lisa Ann posted, cropped Most active or previous Loopers already know this, but for those who don’t….Our, PerfectSeas new leg of the trip is the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway. It started athe the pool level of Pickwick Lake in Tennessee and runs downhill into Mobile Bay. We will lock down 341’ over the distance of 450.4 miles to Mobile Alabama. The rivers currents are with us at a whopping 0.5 knots. There are 3 sections to the waterway, the divide cut, where Pickwick Lake is 414’ above sea level, the canal section, consisting of dams and pools connected to form a 9’ deep waterway along the canal, and repeats the process to the 6th and final lock. The last part of the waterway is called the river, where is was straightened. There will be one more lock in the Black Warrior section. So it’s a total of 10 locks. Nine of them drop us about 30’ and the largest, which we went through yesterday dropped us 84’. This waterway system was proposed back in the 1700’s, but was finally started in 1972. It cost 2 billion dollars, when it was finished in 1985. More earth was moved in this system, than in the Panama Canal system [my emphasis]. Crazy! George Sirk: 13 locks from Pickwick to Mobile. Last one is Coffeeville, which doesn’t show on this map.Joey Ritchie shared |

"The Tenn-Tom was controversial from its inception, and optimistic predictions of its economic benefits by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers never materialized. Originally estimated to cost $323 million in 1970, the total cost at completion in 1984 was almost $2 billion. Funding was approved in 1968. "A combination of environmental groups, the railroad industry, and members of Congress from other regions of the country were successful in blocking funding for years. To much of the public, the Tenn-Tom came to epitomize "pork-barrel politics" at its worst. The estimated economic benefits of the waterway by the Corps of Engineers were derided by opponents as unsupportable based on projected traffic volume, a challenge that later proved to be true. The project was deauthorized at one point, and Pres. Jimmy Carter sought to cancel it." Construction began in 1972 and "proceeded over the next 12 years, consisting of 10 locks and dams and 234 miles of navigable waterway and the excavation of 310 million cubic yards of earth, more than was excavated for the Panama Canal. Eight railroad bridges and 14 highway bridges were either relocated or rebuilt. The single-greatest challenge was the construction and excavation of the so-called Divide Cut. This 29-mile portion of the waterway connected the Tenn-Tom with Pickwick Lake. The cut is 280 feet wide and at its deepest cut required the removal of earth to a depth of 175 feet. This single section of the waterway alone took eight years and required the removal of 150 million cubic yards of earth, almost half of the total excavated for the entire project. The Tenn-Tom encompasses 17 public ports and terminals, 110,000 acres of land, and another 88,000 acres managed by state conservation agencies for wildlife habitat preservation and recreational use. The elevation change between the two ends of the waterway is 341 feet, or a drop of 1.46 feet per mile....Prior to its construction, however, the Corps of Engineers predicted that the waterway would float 27 million tons in its first year of operation. As the result of a variety of fluctuating economic conditions including low demand for coal and loss of overseas markets grain, however, the Tenn-Tom has peaked at only about 8 million tons per year thus far." And coal and timber was 70% of that peak. [EncyclopediaOfAlabama]

The locks are the same 600'x110'x9' standard as the Upper Mississippi and Illinois River waterways.

I learned of this waterway from a Sept. 20, 2019, Chicago Tribune Article by Jay Reeves with the headline: "From hope to South’s ‘big ditch’." The sub-headline was: "$2 billion shortcut to Gulf of Mexico fails to yield boom."

The waterway was closed in March, 2019, because of sandbars left by flooding. It cost $10m and three weeks to dredge an emergency access channel to the lock at Aberdeen. [USnews]

The locks are the same 600'x110'x9' standard as the Upper Mississippi and Illinois River waterways.

|

| USACE The Divide Cut under construction in the early 1980s |

I learned of this waterway from a Sept. 20, 2019, Chicago Tribune Article by Jay Reeves with the headline: "From hope to South’s ‘big ditch’." The sub-headline was: "$2 billion shortcut to Gulf of Mexico fails to yield boom."

The Corps and supporters justified the spending with predictions that shippers would send 29 million tons up and down the Tenn-Tom annually, and the opening ceremony proclaimed it the pathway “to a dream of orderly growth and prosperity for all the people of this region, and for the nation as a whole.”

Corps statistics show an average of 7.2 million tons of cargo traveled the Tenn-Tom annually over the past decade, just a quarter of the initial forecast. By comparison, 304 million tons of cargo went up or down the Mississippi River, which can accommodate larger loads, over the same period.

“It’s the lack of development. It just hasn’t been what they thought it would,” said Mitch Mays, administrator of the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway Development Authority.

Alabama and Mississippi are renewing efforts to promote the Tenn-Tom, he said.

Officials say there’s no single reason companies didn’t flock to the waterway. The rise of overseas industry hurt domestic businesses just as promoters were trying to sell the Tenn-Tom as a new route. Some blame the decline of coal and poor promotion for the lack of growth; others cite an inadequate workforce and the inertia of generational poverty.

“The poor counties that were poor and were in poverty were that way for other reasons,” said Allison Brantley, who promotes economic development in Sumter through the University of West Alabama.

[ChicagoTribune]

|

| Jay Reeves/AP via Chicago Tribune [A Steel Dynamics plant is one of the few economic bright spots along the waterway. But they built the plant a few miles away from the port.] |

|

| DailyTimesLeaderThis aerial shot shows the shoaling on the Tenn-Tom Waterway just south of the Aberdeen Lock and Dam.

It will take six to eight weeks for a short-term fix as the Corps of Engineers brings in a dredging crew to remove tens of thousands of cubic yards of silt that has created a massive sandbar that has the river so shallow it’s only about knee deep in spots.

Long-term fixes will take four or five years, according to the Corps chief operations engineer.

The Corps’ in-house rig is clearing a 200-foot long sandbar at mile marker 410 in southern Tishomingo County. That should be finished this weekend. Kentucky Lock on the Tennessee River near where it meets the Ohio also should be cleared by this weekend, as will a clog at Coffeeville, Ala. According to Tenn-Tom Waterway Corps Operations Manager Justin Murphree, the dredging rig should be in place at Aberdeen in three weeks. It’ll take a least three weeks to dredge out 150,000 cubic yards of silt and debris to open a one-lane barge channel. The sandbar that has closed the river is made up of an estimated 400,000 cubic yards that will take much longer to remove.

Murphy and veteran river watchers say the shoaling that has blocked the river has never happened before in the 35 years since the waterway opened. And they don’t see this episode as a sign of a long-range problem or channel issue. “This is a once in a generation type thing. Even the carriers say they’ve never seen this in 44 years of being on the rivers,” Mays said.

“There’s going to be a big reduction in tonnage because of this. And part of the federal money we get is based on tonnage. That’s one of the things Mitch is talking to them about. This has long-range implications,” added Agnes Zaiontz, the business manager for the Tenn-Tom Waterway Development Authority.

|

The waterway was closed again in Sept, 2019, because an barge accident created a hazardous oil spill in the Jamie Whitton L&D at Bay Springs Lake. "The oil is contained inside the lock and the Corps of Engineers said there is no threat outside of the lock area." [WTVA]

This map shows what little impact the waterway has had on barge traffic. The numbers for the scale are 250, 125 and 62.5 million tons per year. And the intercoastal waterway, except between Texas and New Orleans, is not used unless pleasure boats use it.

This map shows what little impact the waterway has had on barge traffic. The numbers for the scale are 250, 125 and 62.5 million tons per year. And the intercoastal waterway, except between Texas and New Orleans, is not used unless pleasure boats use it.

|

| WashingtonPost, 2016 |

For future reference, a list of hydropower facilities in the Mobile District.

|

| USACE via USACE |

|

| USACE-TennTom posted On this day in 1984 construction was completed on the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway! The photo below is called "Historic Meeting of Two Rivers" from a National Geographic article published in 1986. It features the historic meeting of water from the Tennessee River, foreground, joining the Tombigbee River near Amory, MS. Photo by: Sandy Felsenthal Pickwick Lock shared Joe Clark: Glad this was completed using the plan b method. Although I am sure the nukes would have been more exciting. [That is a BNSF/Frisco bridge in the background.] |

The Mississippi River and the fifteen road and six railroad bridges that cross it are part of a regional transportation net the developed between 1800 and World War II. The story of bridges in the Upper Tombigbee river valley is part of the story of the changing relationships between the river, the railroads, and the highways in NE Mississippi. The first settlers of European stock reached the area when Robert Fulton and others were perfecting the steamboat. During the 19th century, the river was variously and simultaneously the principal avenue of transportation and its chief obstacle. The ante-bellum riverboats carried the bulk of commerce; landings spotted the riverbank, and some became villages only because bad roads and river crossings made the towns inconvenient. The railroads were first conceived of as feeders to the river; in the end they entirely supplanted it. The highway bridges linked the towns with their hinterlands and made the railheads as convenient as the riverbanks. By the time Henry Ford had sent the automobile swarming across the continent, the Tombigbee was irrelevant as thoroughfare or obstacle.-- Historic American Engineering Record[BridgeHunter]

24:35 video of the history of the Tenn-Tom Of note at 6:48 is the "chain of lakes" construction used in the canal section. This is one of them. The upper reach of steamboat navigation was Cotton Gin Port. [7:13] My current understanding is that was at Amory, MS. I'm confused because the locks have been renamed since this video was made.

When you see what the original river looked like back in the steamboat era, it continues to amaze me how far they travelled inland before railroads and paved roads were developed. (Although this may have been just upstream of Cotton Gin Port.)

|

| USACE |

I was surprised that the Tenn-Tom looks about as crowded as the Mississippi. Is that because the Mississippi is low and some tows are using the Tenn-Tom as an alternate?

|

| 16:58 video @ 0:45 |

Great job....

ReplyDelete